If you participated in Field Day 2019 at Ensor Park and Museum on Saturday, June 22, you helped amateur radio pioneer Marshall Ensor of W9BSP fame celebrate his 120th birthday, albeit in his absence unfortunately and likely, on your part, unknowingly.

Born June 22, 1899 in Johnson County, Ensor demonstrated an above-average ability as a woodworker at an early age and won a first place prize in 1915 for the kitchen cabinet he constructed for a national contest sponsored by the Simond Saw Company. He also displayed a real interest in wireless telegraphy, or radio, as a teenager and in 1916 built a spark gap transmitter that enabled him to communicate with others through Morse code at a distance of up to 20 miles.

After his graduation from Olathe High School (now Olathe North High School) in 1917, Ensor was hired to be an assistant under Manual Arts instructor James Bradshaw during the 1917-1918 school year. The following term, 1918-1919, the teaching position was his, as Bradshaw had moved on.

In 1937, and this is further evidence of the impressive creative talents Ensor possessed, he constructed an illuminated wooden scoreboard for use at OHS home basketball games. There was a two-dimensional likeness of an eagle, the school mascot, atop the scoreboard, and Ensor even managed to put a little light in the eagle's eye that continued to shine with determination during games, even when the good guys or the good gals weren't doing so good on the court.

Meanwhile, the first-in-Kansas high school Radio Club that Ensor had started 11 years earlier in 1926 was still going strong, sending and receiving messages over the airways as W9UA under the trusteeship of his younger sister, Loretta, who was 9UA when she became a licensed amateur radio operator in 1923 shy of her 20th birthday.

Ensor would go on to teach at the 'electric' home of the high-flying Eagles in three additional decades, 46 years in all, stepping away from the classroom only twice, in 1932 to attend Kansas State Teachers College of Pittsburg (now Pittsburg State University) to work on a bachelor's degree, and from 1943 to 1946 while he served as an electronics officer at the Naval Air Station in Seattle, Wash., during World War II. According to the Feb. 28, 1970 issue of The Daily News of Johnson County (now The Olathe News), "his work on high frequency direction finding helped break up the German submarine 'wolf packs'" that had been a constant threat to the ships of the Allies earlier in the war.

In the 1950s and on into the '60s, Ensor's students received many awards for the fine pieces of furniture they built from scratch under his watchful eyes, often using wood that had been harvested from the trees on the Ensor family dairy farm south of Olathe along 183rd Street. One of Ensor's students in those days was Thomas Brown, who turned out a handsome-looking rocking chair that was accepted by The White House on behalf of President John F. Kennedy.

And off the school 'campus' east of Olathe's courthouse square, Ensor was instrumental in the establishment of the first Civil Defense organization in Kansas during the years that followed WW II, when the so-called Cold War had Americans legitimately fearing an all-out nuclear strike by the Russians.

In 1922, just five years into his career in the field of education, Ensor became a licensed amateur radio operator and the call sign 9BSP was assigned to him by the Department of Commerce, which preceded first the Federal Radio Commission and then the Federal Communications Commission as the agency charged with the task of issuing licenses. Five or so years later, as a result of the mandated addition of the "W" prefix to call signs, he was W9BSP.

Ensor's original station was located in the busy kitchen of the two-story Italianate home he shared with his parents, Jacob and Ida Ensor, and his sister. A secretary desk contained his battery-powered rig with its ever-present vacuum tubes.

Responding to an invitation that had been extended to amateur radio operators across by the country by the American Radio Relay League, Ensor began teaching Morse code and radio theory over the airways 90 years ago this month. The plan was for him to give a one-hour lesson each evening during the months of December and January, the combination of nighttime, a favorable time of day, and winter, a favorable season, being the one most likely to allow signals to travel through the ionosphere from fixed Point A, the new Radio Room on the east side of the house, to variable Point B, the homes of the men, women and teenagers who were faithfully listening to his broadcasts in the Midwest and elsewhere. On occasion his sister had to fill in for him for some reason, but between the two of them, they presented lessons every evening over a two-month period without fail from December of 1929 up until Dec. 7, 1941, the day the Japanese attacked the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor.

By then, Ensor had equipped an estimated 10,000 Americans with the skills and knowledge they would need in order to pass their tests to receive a license from the FRC or the FCC. More important, he had trained any number of young men to the point where they could serve effectively as radio operators and electronics specialists in the Armed Forces during the Second World War, then experience success in the private sector following the war.

In view of the service to his country he had performed in providing radio lessons free of charge to thousands of his fellow citizens, Ensor was selected to receive the William S. Paley Award for 1940 and it was bestowed upon him in 1941 during a gala ceremony at The Waldorf Astoria in New York City. The ceremony, also attended by his sister, was carried live over the Columbia Broadcasting System headed by Paley.

The Radio/Electronics Club that Ensor organized at OHS gave students the opportunity to pursue their various interests in the field of electronics and acquire valuable, and potentially marketable, skills at the same time. One of those students was future Santa Fe Trail Amateur Radio Club Secretary-Treasurer Marty Peters, KE0PEZ, who was a sophomore during the 1963-1964 school year.

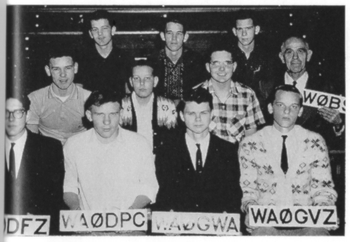

In the photograph accompanying this story, which was taken for the 1964 OHS Eagle, Ensor, who retired in 1965, is pictured on the right on the middle row holding a placard bearing his post-WW II call sign, W0BSP, while Marty is on the left on that same row. The two boys between them are Ed Badsky, second from the left, and Richard Birnell. The front row consisted of Terry Smith, WA0DFZ, Dick Whitehouse, WA0DPC, Larry Thomas, WA0GWA, and Norman Brady, WA0GVZ, the back row of John Fittell, left, David Lunday, center, and David Cochran. Like Ed, Richard, John and the two Davids, Marty wasn't a licensed amateur radio operator when the photo for the yearbook was snapped, but he told me recently that he received his 'ticket' a short time later in the spring of 1964 after taking, and passing, the test administered to him at the "federal building" in downtown Kansas City, Mo. He was WA0IZD back then. "I decided to go for General right from the beginning," he said, pleased with his choice of possible licenses to pursue at that point in his life. In those days, he related, an individual had to be able to decode at least five words a minute transmitted in Morse code to qualify for a Novice license, 13 words a minute to earn a General license, and 20 words a minute to get an Extra license. A word was defined as five characters, so an individual had to accurately decode at least 65 characters in a row within a five-minute period to be eligible for the General license. Marty said members of the Electronics Club met for "about an hour" once a week after school, gathering in a side room off the main room in the shop. He said they would sit in a circle and that Ensor, seated with them, would ask he and the other boys a series of questions, questions pulled from the pool of questions that were used in devising the written examinations given to prospective amateur radio operators. After each question, the answer supplied, right or wrong, was discussed to promote learning at a deeper level, and a reply of "I don't know" or "I'm not sure" was a sure-fire way of guaranteeing that there would be a spirited discussion of some sort.

Marty said code practice was a large part of these weekly club meetings and that a machine similar to a reel-to-reel tape player was employed to help the boys learn the different letters and numbers. "It was kind of a straightforward, matter-of-fact approach," he observed in recalling the experience.

According to Marty, the machine used a paper tape as opposed to a plastic tape, and the tape was white but it had a black line running through it whose position was always changing depending on whether the sound of a "dit" or the sound of a "dah" needed to be produced by the machine at a given moment. The tape was illuminated by a light and if that black line didn't block the light emitted, the light passed through the tape to a light-sensitive detector, causing the machine to generate either a tone for a "dit" or a tone for a "dah". The speed at which the tape moved could be adjusted from one student to the next, thereby letting a student who was just learning the Morse code practice at a relatively slow speed before he turned the machine over to a more advanced student who wanted to practice at a higher speed.

Reflecting on those days, Marty recognized at once that Ensor was a teacher who was truly committed to the work he did day after day in the classroom and beyond it, to equipping generations of Americans with valuable radio communication skills that included proficiency in Morse code, and to opening their eyes to a world of future possibilities in electronics and other fields. "He knew how important it was," he said.

Marty described the Marshall Ensor he knew as a thoughtful, soft-spoken man with "a quiet demeanor" who exhibited patience with he and the other boys as they delved deeper and deeper into the world of voltage, current, circuits, Ohm's Law and the like. "Nobody was made to feel foolish," he related.

Greg Sheffer, on the other hand, would describe the Marshall Ensor he never knew as a renaissance man and did, in fact, in producing the short film "Renaissance Man", a presentation focused on the life and times of Ensor, for the Olathe Historical Society in the early 2000s.